* * * * *

We also desperately

needed a first officer (co-pilot), so I rang up Toa in Bangkok, the Thai kid

that flew as my first officer in Vietnam.

He happily joined us and easily filled in that slot.

Oh,

yes, dear reader, some Southeast Asian airlines maintenance-wise were that bad.

F.A. Pootong was fluent in four languages: Laotian, Thai, English and Russian. She was a graduate of a Moscow University.

Regarding maintenance at Lao Aviation for our B-737, we had an excellent, ex-Lufthansa German mechanic, named Peter, and Donny an ex-US Army mechanic.

Donny was a Vietnam Vet who got sick of the killing one day and “walked off the job.” He settled in Laos with a Laotian wife, living quietly in her village without a passport or visa. The Laotians readily accepted him, because he never caused trouble and could fix broken mechanical equipment; keeping the village humming along.

Donny on the cockpit’s jump seat. Occasionally he’d ride with us to trouble shoot any mechanical issues.

Peter and Donny also kept our single 737 humming right along, and for any heavy-duty inspections or parts replacement, we’d run the 737 over to Bangkok for the night, where Thai International’s Maintenance Department would handle it. I never had a single complaint with the maintenance.

However, the 9,843-foot runway at Vientiane’s

Wattay International, was another matter.

Instead of a nice, long, smooth asphalt surface, it was made up of long,

rectangular concrete slabs; similar to what the Russians hastily threw together

during WWII. Resulting in a runway like

a washboard, which could jar one’s teeth loose as it was so rough on

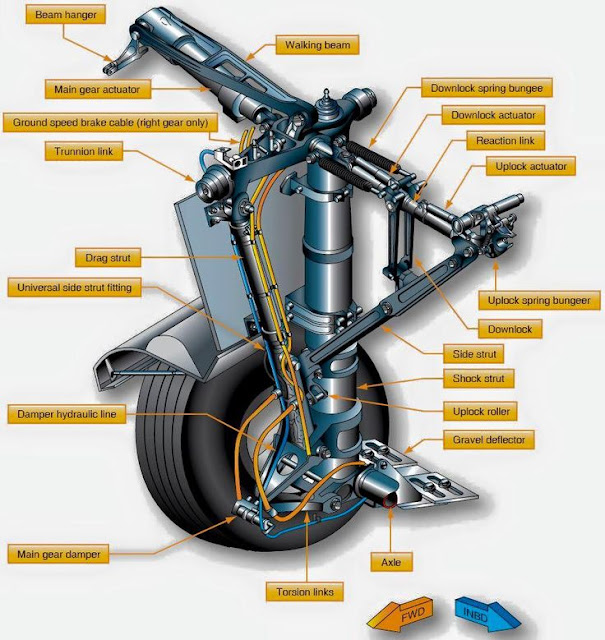

takeoff. What I really worried about was

the shock strut on the nose wheels, taking the brunt of the pounding, hitting

against its metal stops. A recipe for

metal fatigue cracks.

When Capt. Fred arrived, we got our heads

together and decided to develop a modified version of the rough-field-soft-

field takeoff technique we learned as student commercial pilots, way back in

the Stone Age Sixties, in the single-engine Cessna 150.

After lining the 737 up on the runway for

takeoff, we’d select flaps 25, pull the control wheel all the way back into our

gut, and then apply takeoff thrust. At

around 80 knots, the nose wheels would lift off the ground, and we’d prevent

them from going any higher; merely wanting them to no longer make contact with

the runway. Now it was a waiting game,

as we rolled down the runway on our main wheels, whose oil-air shock struts

absorbed the pounding, with our nose in the air, snootily at roughly a

30-degree angle.

Frankly,

dear reader, it felt good. The nose

wheels were no longer pounding themselves to death. And, at this high angle of attack, I could

actually “feel” the wings generating lift, as we accelerated, transferring the weight

of the 737 from the main wheels to the wings; transitioning from a ground

machine to an air machine.

Just after passing V-1, our 737 would lift

smoothly into the air all by itself; we already had the proper angle of attack,

so we didn’t have to do a damn thing. Almost

immediately we’d pass V-2 and retract the landing gear, accelerate rapidly as

we climbed, and ultimately retract the flaps on their speed schedule.

It

was a “piece of cake,” dear reader, giving our passengers a silky-smooth ride.

As a historical footnote: The infamous Air America operated a mixed bag of fixed-wing and helicopter aircraft, out of Vientiane’s Wattay Airport from 1959 to 1974; supporting the CIA’s “Secret War,” under the code name “Operation Momentum,” by transporting food (Rice Drops) and weapons (Hard Rice) to the Hmong mountain tribes that were fighting the Communist Pathet Lao.

Air America's

slogan being: "Anything, Anywhere, Anytime, Professionally."

While engaged in this activity, in 1968, Air America performed an “aviation first.” On 12th January, four North Vietnamese Air Force AN-2 Colt biplanes arrived at a mountaintop US radar base, “Lima Site 85” in northern Laos, with the intention of strafing and bombing this site. As luck would have it, shortly after their arrival an Air America UH-1D Huey helicopter, carrying ammunition to this site, also arrived. The helicopter pilot coordinated with his “kicker” in back, and deliberately flew over two of the big, slow, single-engine Russian-built biplanes. Whereby the “kicker” leaned out of the opened, left side door, and sprayed each of the biplane’s cockpits with AK-47 fire!

Apparently the “kicker”

either seriously wounded or killed the pilots, as both biplanes consequently nosed

over and crashed; abruptly ending the Vietnamese bombing raid of the US radar

base! Within hours a

This

was an aviation historical (hysterical?) first: a helicopter shooting down two fixed-winged

bombers! Who says the Air America flight

crews were “cowboys,” dear reader?

*

* * *

*

Comments

Post a Comment