* * * * *

Hanoi,

Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV)

Tuesday, 28th November 1995

Hanoi was occupied by the French in

1873 and was the capital of French Indochina after 1887. The city was occupied by the Imperial

Japanese Army in 1940 and liberated in 1945, when it briefly held the seat of

the Viet Minh government

after Ho Chi Minh proclaimed

the independence of Vietnam. Sadly, the French returned and reoccupied the city

in 1946. After nine years of fighting between the French and Viet Minh forces,

Hanoi emerged as the capital of an independent North Vietnam in

1954. Following the end of the Vietnam War,

with the U.S., Hanoi became the capital of a reunified Vietnam when North

and South Vietnam were

reunited on 2nd July 1976.

And that, dear reader, is my quick

and dirty history on Hanoi.

If you’ll remember, at the beginning of this chapter, I had previously

operated to Hanoi when flying for Pacific Airlines out of Saigon. So this first flight for Lao Aviation was

likened to a tramp down memory lane.

And, what I remembered most about Hanoi was its strange weather. Saigon in the south was generally clear nearly

all of the time, whereas Hanoi, in the north, always had these stubborn layers

of grey, stratus cloud which never dissipated.

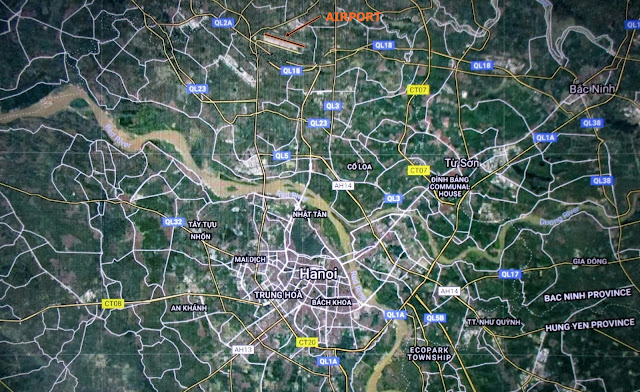

After launching from Vientiane, Laos, and subsequently climbing to 33,000 feet, while taking the R-474 Airway in a northeasterly direction to the Mocchau NDB, we then turned right to a more easterly heading and proceeded direct to the Noibai VOR at Hanoi.

For

my 737 it was relatively a short trip, cruising at 420 knots (483 mph) we covered

the 275 NM (316.2 SM) to Hanoi in forty minutes flat. However, upon arrival Noibai Tower always instructed

us to “hold” at 5,000 feet as they recovered a pair of MiG-21 fighters. Slowing down to my best “clean” speed of 210 knots

(241.5 mph), to conserve fuel in the holding pattern, frustratingly I was

forced to fiddle away another fifteen to twenty minutes.

Approaching the city from the southwest the rugged ranges of mountains

abruptly fell away, revealing Hanoi resting on the south bank of the Red River,

in the flat Red River Delta. Twenty-one

miles northeast of downtown Hanoi, across the Red River, lay Noibai

International, built in January of 1978 immediately south of the Phúc Yên Air Base.

I was required to imagine all this

brilliant description, dear reader, for upon leaving 33,000 feet my 737

commenced to slip through stratus cloud layer after stratus cloud layer; keeping me totally blind as to what was going

on outside; flying solely by instruments.

A this point I became aware of an interesting anomaly

between air traffic control in North Vietnam, as opposed to South Vietnam. The Saigon ATC Controllers spoke English with

an American accent and could radar vector me; obviously having exposure to USAF

instructors during the Vietnam War.

Whereas the Hanoi ATC Controllers spoke with a heavy accent, resembling

English, and could not radar vector me; apparently the by-product of Russian

instructors, which meant I was required to fly the full-blown, antiquated, World

War II instrument approach.

In Addition, as Noi Boi was a secondary Russian MiG-21 base, Noi Boi Tower always had a couple of MiG-21 fighters in front of me, also slogging along blindly in the convoluted instrument approach.

Since there was no rush to get me on the ground, due to these fighters

ahead of me, I was always told to “hold” at the “Kilo” low frequency radio beacon,

one half mile off the runway’s threshold, at 5,000 feet. Therefore I’d usually “hold” in a racetrack

pattern for fifteen to twenty minutes before being cleared to make the

instrument approach to Runway One-One; a runway that was 10,499 feet in length

and ran southeast to northwest (110°/290° magnetic) with an ILS Approach.

From November 1995 to May 1996, I made 17 round trips to Hanoi, and the

above requirement to “hold” was always the same followed by a landing on the

same runway. As all these “same” trips

blended into my grey matter as one oversized bore, I can barely recall two

events that broke this boredom.

If memory serves me correctly it was perhaps in mid-January of 1996, that I arrived over the “Kilo” radio beacon as usual to begin “holding” at 5,000 feet, when I was surprised to discover I wasn’t alone. Two thousand feet below me there was a Continental Airlines’ DC-10 also “holding” at the “Kilo” beacon.

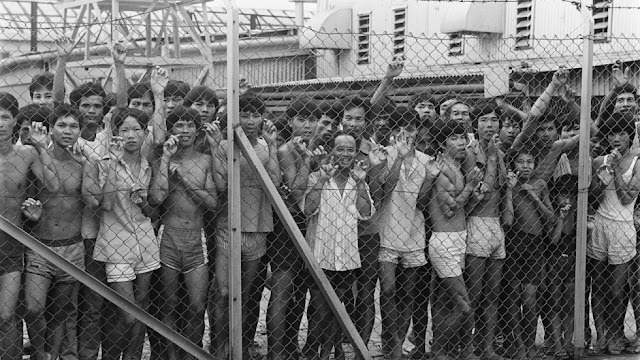

Okay, dear reader, let’s hit “Pause.” What the hell is a U.S. based Continental Airlines DC-10 doing in Vietnam? No doubt you’re asking. Simply this: they were contracted by Hong Kong to forcibly repatriate over 250 Vietnamese “Boat People.” These poor folks had escaped Vietnam over ten years ago, on leaking-sinking vessels, then herded into internment camps with tens of thousands of other Vietnamese, and now, because the Red Chinese Government was about to take over Hong Kong, the Chinese wanted all the Vietnamese “Boat People” ejected back to Vietnam.

Right, so here I am with my seat tilted back, feet

propped up on the foot rests - sipping a cup of coffee the attractive Laotian girl

has just brought me - while having my Thai Co-Pilot, Toa, fly the “holding

pattern” on autopilot. This gave me the

freedom to oversee the big picture, keeping track of our position and the air

traffic around us, despite being contained in a cloud layer blind as a bat. Even so, at this juncture, I became amused.

The DC-10 is “holding” for a pair of MiG-21s landing in front of it, and

every two minutes the DC-10 Co-Pilot kept asking the Noibai Tower for an

“Expect Approach Time.” To which the

tower gave the age old Asian stall, by saying, “Standby...”

Obviously the DC-10 crew hadn’t planned on this additional delay, and

were getting mighty short on fuel, for each time the DC-10 called the tower,

the pilot’s verbal pitch got higher and higher; I could actually hear his

panic. And every time the DC-10 asked for

an “Expect Approach Time,” what did the tower reply?

“Standby...”

So why do I find this amusing, dear reader? These States-side pilots were obviously new to Asia; where Chinese Dispatchers out of Hong Kong always try to shortchange pilots on fuel. I, on the other hand, am wise to the game and always tanker extra fuel for the Hanoi run to deal with the “holding” problem, and any other unforeseen commie delays. Hell, I’ve presently got enough fuel on board to take us all the way to Bangkok and back. So I kept my 737 clean and slow in the racetrack “Holding Pattern,” conserving fuel, and rang the girl for another cup of coffee; chuckling to myself over the plight of these green Continental pilots. Welcome to Southeast Asia fellows.

Ultimately, the DC-10 made it on the ground okay, sucking fumes, with

their very unhappy human cargo.

As for me, dear reader, not being

a nice person, I always enjoy witnessing history in the making.

Another event that stands out in my grey lump, three

feet above my ass, occurred on a Hanoi trip in April of 1996. After touching down on Runway One-One, as

usual, and proceeding to backtrack on the taxiway south of the runway to the

center of the airfield, where the usually empty parking apron lay, I was

surprised to spy a humongous transport near my parking spot.

May I explain my surprise, dear

reader? Tough...here it is anyway. So far Hanoi Noibai Airport had proven to be

another Communist ghost town. There was

never any movement of air traffic or vehicular traffic to be seen on the aprons;

only a few trucks parked near the rundown terminal, and the usual string of

MiG-21s parked on the other side of the runway towards its end.

As I drew closer to the mainly empty, massive-concrete apron, the huge

transport took the shape of a Lockheed C-141 “Starlifter,” having four

turbo-jet engines, and bearing the markings of the USAF.

So please tell me, dear reader,

what the Devil was the American Air Force doing here in Vietnam; crowding my usual

parking position?

I deliberately swung behind the C-141, as close as I

dared, observing its rear loading ramp was down, and as I passed behind it I

glanced inside its enormous, black, empty cavern-like fuselage. Parking my 737 fifty meters from the C-141’s

right-rear quarter, I transferred all electrics and air conditioning over to

the APU, and shut down both my turbo-jet engines.

After securing the cockpit, and deplaning the passengers, I told Toa, my

Thai Co-Pilot, to remain in the cockpit while I did the post-flight “walk-around.” This was normally his job, but Toa was happy

to relax in the cockpit, and set everything up for our return flight to

Vientiane.

No, dear reader, I’m not being a

“nice guy,” I wanted a closer look at that USAF C-141.

As I slowly began my inspection of the 737, looking for breaks, leaks,

or anything important falling off the aircraft during our flight here, I kept

fifty-percent of my attention on the C-141 and the activity surrounding it.

A long, white, portable table had been set up off the C-141’s right

front quarter. Several men in black

business suits were shuffling paperwork and inspecting five, brown, wooden

boxes, roughly the size of microwaves.

Now I’m really stumped, dear

reader. Why on earth would the USAF send

such a monstrous transport to obviously pick up these small boxes? What was so important in these boxes?

When a group of U.S. Servicemen, in dress uniforms

representing all branches of the armed forces, abruptly appeared, it all

stunningly became crystal clear; solving my mystery.

Utterly transfixed, I stopped my post-flight inspection as I respectfully stood frozen to the ground; being witness to a very moving ceremony.

With great care the uniformed U.S. Servicemen transferred the wooden

boxes to five, individual, full-sized aluminum caskets. They draped the caskets with the American

flag, then, acting as pallbearers, they individually carried the caskets aboard

the C-141.

These boxes contained the remains of American servicemen that had gone MIA during the Vietnam War; hence the outsized, C-141 transport with the guard of honor.

After witnessing this ceremony, I was prompted to do a bit of research,

and this is what I learned on the “MIA Facts Site.”

This is a quote from that site:

“Summary. For years, U. S.

analysts and policy makers knew that the Vietnamese had in place a process of

burying Americans who died in captivity or whose remains they recovered.

We also knew that the Vietnamese recorded the condition of recovered remains

and the location of burial sites. There was unmistakable evidence that

the Vietnamese recovered American remains, processed the remains (cleaned and

in some cases treated with preservatives), stored them, and eventually returned

the remains to us.”

As I watched the caskets being

carefully loaded into the C-141’s black bowels, dear reader, I said a simple

prayer in my heart that these remains would at last bring peace and closure to

the MIA servicemen’s families and loved ones.

Vietnam Veteran’s Memorials, Washington, DC.

* *

* * *

Comments

Post a Comment