* * * * *

As I mentioned before, it was a fantastically clear night, thank God, and eventually I could observe the jewel-like lights of Miami on the horizon with the stars beyond. Directly below and ahead was the black abyss of the everglades – issuing no lights whatsoever - conversely emphasizing the jeweled-beauty of Miami in the distance.

And at this instant, dear reader, a very odd sensation engulfed me - prompting a chill to climb my spine.

An event that occurred on 29th December, 1972, came to mind. An Eastern Air Lines Lockheed L-1011 TriStar crashed here at the everglades, at 11:42 P.M., causing 101 fatalities and leaving 75, badly banged up, survivors. The crash occurred as a result of the flight crew becoming preoccupied with a burnt-out landing gear indicator light, and failing to notice the autopilot had inadvertently been “bumped” to the CWS (Control Wheel Steering) mode. Subsequently, while the flight crew was distracted with the indicator problem, the aircraft gradually lost altitude and crashed. It was the first crash of a wide-bodied aircraft and, in 1972, the second deadliest single-aircraft disaster in the United States.

As I reflected on this accident, dear reader, it consequently occurred to me that we were retracing this ill-fated TriStar’s route above the everglades. The current view I was enjoying of our approach to Miami, was the identical view the doomed TriStar crew had experienced; hence my chill.

Miami Approach Control radar vectored us to intercept the localizer for Runway Nine Left (090°/270° magnetic, East/West), just as it had done for the ill-fated TriStar. Although this furthered my discomfort, I shoved these feelings aside, disconnected the autopilot and concentrated on the approach as I flew it “by hand.”

Each time when I called for flaps, I noticed the captain still had the “shakes” as he reached for the flap lever. This was distracting. When I called for the landing gear, shaking badly, the captain reached for the gear lever and lowered it. This was also distracting. As I called for these items, I had to increase both throttles a little, to make up for the additional drag, so I wouldn’t lose airspeed. When I did this - the pressurization surged abnormally and gave our ears a “bump” - additionally finding it distracting as hell!

Gritting my teeth, dear reader, I employed FTFA (Fly The Fucking Aircraft) – determined not to allow any of these distractions break my concentration.

Miami International Airport.

On Final Approach to Runway 9 Left at Miami.

I had already intercepted the Localizer – lining us up perfectly down the center of the runway. When we intercepted the Glide Slope - after lowering the landing gear - I only called for “Flaps Thirty” to comply with the noise abatement procedures. Using Flaps 40° required extra power – producing additional noise. And as I adjusted both throttles to maintain Vref (Landing Speed) for Flaps 30° - getting another pressurization “bump” – that’s when it really got distracting.

At this point we had previously switched to the tower frequency, and were five nautical miles from the end of the runway, when we heard Miami Tower clear an Eastern B-727 for takeoff in front of us on the same runway. A bit later, I saw the Eastern tri-jet, lit up by its strobes and landing lights, slowly enter the runway and commence its takeoff roll. I increased power slightly - adding another five knots to my Vref – anticipating the turbulent air left behind in the tri-jet’s wake - receiving another pressurization “bump” on our ears for my efforts.

As we descended to 300 feet, and barely a mile out from the end of the runway, the Eastern tri-jet announced via the radio that he’s aborting the takeoff! At that moment I realized the tri-jet, which hadn’t left the runway yet, is actually slowing down in front of me!

Holy crap!

Immediately I called for, “Flaps Fifteen,” as I advanced both throttles to “Climb Power,” while raising the nose marginally. Now the captain’s hand was severely shaking as he raised the flaps to 15°. Getting a positive rate of climb on my flight instruments, I called for, “Gear up!” Shaking wildly, the captain raised the gear lever – retracting the landing gear.

Miami Tower then radioed us, saying: “Washington Eagle go-around! Climb to three thousand feet and report downwind of runway nine left.”

As his hand-held mic wobbled palsy-like, Captain “Shaky” repeated their instructions over the radio.

I leveled out at 800 feet, accelerated, and called for “Flaps Up.” Shaking spastically, the captain raised the flaps. Accelerating to 210 knots, I climbed to 3,000 feet – then throttled back to maintain speed and altitude - afterwards banking left and rolling out downwind to parallel Runway Nine Left.

In reality this is getting quite spooky, dear reader, for I am replicating the very flight path of the ill-fated Eastern Flight 401. Because the TriStar had also made a missed approach to Runway Nine Left - when it failed to get a nose gear “Down and Locked” indication – on the night it crashed in the everglades.

I am now replicating the flight path of the doomed Eastern Airlines Flight #401.

After I pass the runway off my left side, the world that lies before me is a black abyss – issuing no lights whatsoever. The exact view of the everglades that the ill-fated TriStar crew had – making it utterly impossible to visually gage speed or height outside.

I must rely solely on my flight instruments, dear reader. FTFA – ignore all distractions. I refuse to use the autopilot – I want immediate hands-on control.

I did, however, steal a furtive glance at our “hitchhiker” on the jump seat - to see if he was okay. He gave me a look that said, “Gee...I wish I had taken the train, the bus, or the boat.”

Yeah, buddy...you and me both.

EAL Flight #401 about to crash in the everglades.

Somewhere up ahead of me, in all that blackness, laid the ill-fated TriStar’s crash site – brought down by the crew being distracted - I was headed right for it.

In the aftermath of Flight 401’s crash, Eastern was confronted by another problem, which they diligently attempted to sweep under the rug. Cannibalizing the broken TriStar’s parts, Eastern placed these parts on other TriStars in their fleet. And that’s when the following started to happen exclusively on TriStars carrying these parts: Reputable crewmembers and passengers began reporting both sightings, and conversations, with the captain and flight engineer from the ill-fated Flight 401. The problem was both of these gentlemen had perished from this crash. Even an Eastern vice president had a conversation with the captain. Afterward both he and a stewardess observed the ill-fated captain “dissolve” before their eyes!

Naturally all manner of books, articles and films made hay with 401’s “ghost stories.”

The “ghosts,” the Flight Engineer and Captain of Flight #401.

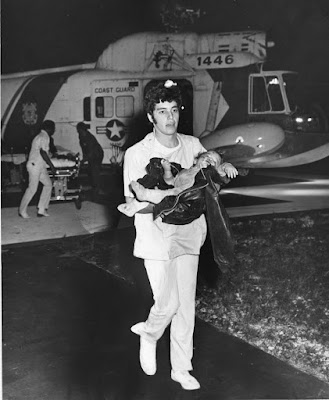

This snapshot was taken on the day of the crash of the Stews. Two of the girls perished, the rest survived their injuries.

This baby also survived.

Eastern Airlines Flight 401’s remains in the everglades.

That “chill” commenced climbing my spine again, dear reader. So I flushed all thoughts of crashes and ghosts from my grey matter – FTFA.

* * * * *

Comments

Post a Comment